From Nursery to Neighborhood: Cultivating Community at Highland Park

Ellwanger & Barry Mount Hope Nurseries, ca. 1901. Image from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library.

From Nursery to Neighborhood: Cultivating Community at Highland Park

By: Megan Hillyard

In the nineteenth century, few enterprises shaped Rochester’s identity as profoundly as Ellwanger & Barry. At a time when Rochester was earning national recognition as the “Flower City,” the firm’s nursery operations along Mount Hope Avenue stood at the center of a booming horticultural economy. What began as a plant nursery would, over more than a century, transform into a landscape of public parkland and residential neighborhoods—leaving an enduring imprint on Rochester’s physical and cultural fabric.

A Nursery of National Prominence

Founded in 1840 by George Ellwanger and Patrick Barry, Ellwanger & Barry rapidly grew into one of the most prominent nurseries in the United States. Their Mount Hope nursery encompassed extensive acreage south of downtown Rochester, where rows of fruit trees, ornamental shrubs, evergreens, and experimental plantings were cultivated for national distribution. The firm’s illustrated catalogs circulated widely, supplying estates, institutions, and municipalities across the country and helping to define American horticultural taste.

The nursery’s success was not merely commercial – it was intellectual and cultural. Ellwanger and Barry were leaders in horticultural experimentation, authorship, and advocacy, helping to shape American tastes for ornamental landscapes and productive gardens alike. This contributed directly to Rochester’s reputation as a center of plant cultivation, research, and innovation. Their nursery grounds along Mount Hope Avenue were both a working agricultural enterprise and a carefully arranged landscape, blending utility with aesthetics in a way that foreshadowed later park design principles.

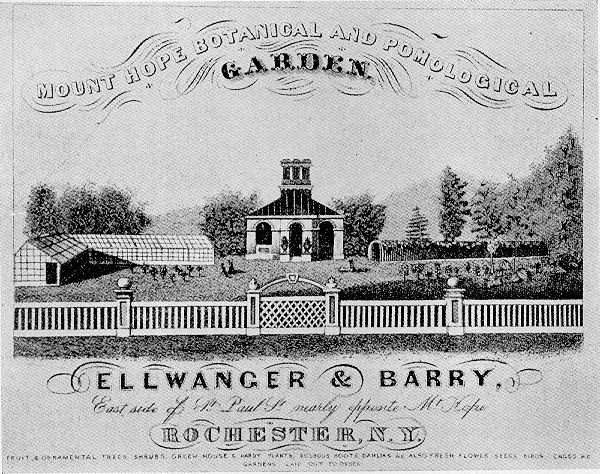

Ellwanger & Barry’s Mount Hope Botanical and Pomological Garden ad, ca. 1855. Image from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library.

A City Expands—and So Does Vision

By the late nineteenth century, Rochester was undergoing rapid change. Industrial growth, population increases, and expanding transportation networks pushed development southward toward the nursery lands. At the same time, shifts in agricultural practices and land economics made large urban nurseries increasingly difficult to sustain. Ellwanger & Barry recognized that the future of their enterprise lay not solely in cultivation, but in thoughtful adaptation.

In fact, this transition began earlier than is often recognized. As early as the 1850s, Ellwanger and Barry began subdividing some of the oldest portions of the nursery for residential development along Mount Hope Avenue and Linden and Cypress streets, recognizing the growing value of real estate at the city’s edge. Their involvement as organizers of the Rochester City and Brighton Railway Company—the city’s first horsecar franchise—further reinforced the connection between transportation, accessibility, and land development, laying the groundwork for later, more extensive real estate efforts.

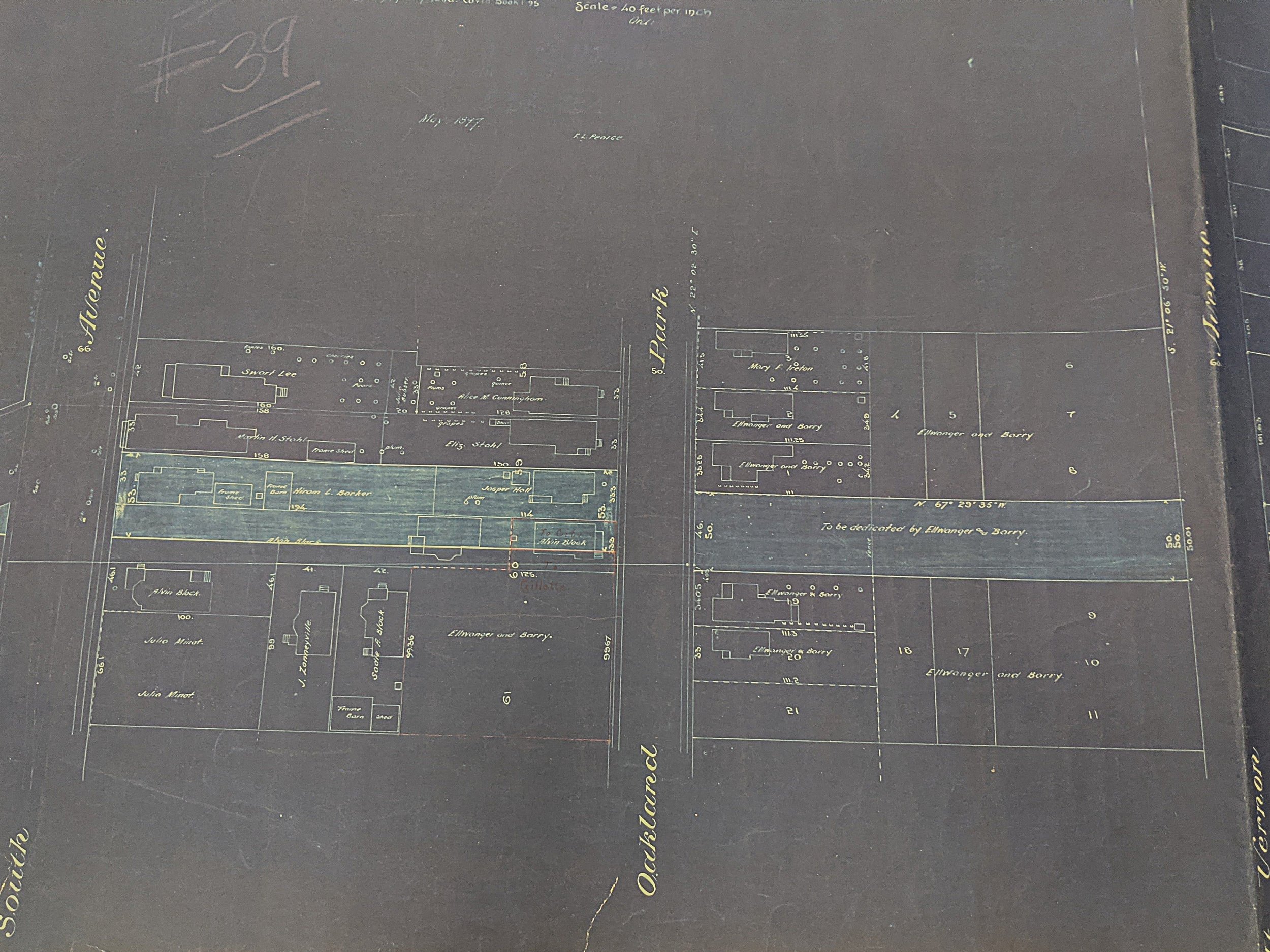

Plans for the extension of Linden Street from South Avenue to Mt. Vernon Avenue ca. 1897. Drawing photographed from the Ellwanger and Barry Papers collection at the University of Rochester, Rochester, New York.

A Gift to the City: The Creation of Highland Park

One of Ellwanger & Barry’s most lasting contributions came not through private development, but through philanthropy. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, George Ellwanger and Patrick Barry donated substantial portions of their former nursery lands to the City of Rochester for the creation of a public park. This gift ensured that a significant portion of the landscape would remain open and accessible, even as the surrounding city continued to grow.

On October 8, 1888, the City of Rochester engaged Frederick Law Olmsted, whose firm was shaping park systems across the country, to design a park system in Rochester. Olmsted’s design for Highland Park embraced the site’s dramatic topography—its hills, ridges, and sweeping views—while integrating curving drives, scenic overlooks, and spaces for horticultural display. Centrally located within the park’s upper elevations was the Highland Park Reservoir, constructed in 1875 as part of the city’s growing municipal water system. The reservoir, with a storage capacity of approximately 26 million gallons, was designed to take advantage of the site’s natural high points and remains a defining feature of the park’s landscape.

The park was formally established in the late nineteenth century as part of Rochester’s growing park system, one that would expand incrementally over time. Ellwanger & Barry’s influence extended beyond the land itself. Many of Highland Park’s early trees and shrubs were supplied directly from the firm’s nursery stock, transforming former rows of cultivated plants into an arboretum-style public landscape. Evergreen collections, flowering shrubs, lilacs, and specimen trees reflected both Olmsted’s design philosophy and the horticultural expertise that had long defined the site.

In addition to its recreational and scenic role, Highland Park has long served an essential civic function. The Highland Park Reservoir, along with Cobb’s Hill Reservoir, plays a critical role in Rochester’s drinking water system. Water from Hemlock and Canadice Lakes is treated at the Hemlock Water Filtration Plant and gravity-fed through Rush Reservoir—located approximately nine miles south of the city—before reaching Highland Park for storage and distribution. This infrastructure underscores the park’s dual role as both a designed landscape and a vital component of the city’s public utilities.

View of Highland Park Reservoir from a lift at a celebration of Olmsted’s 200th birthday and Children’s Pavilion reconstruction announcement. Photograph courtesy of The Landmark Society of Western New York.

From Nursery Rows to Residential Streets

As Highland Park emerged as a public landscape, the surrounding former nursery lands continued their transformation into residential neighborhoods. Beginning in the 1880s and 1890s, Ellwanger & Barry gradually transitioned toward real estate development through the Ellwanger & Barry Realty Company. Rather than rapidly liquidating their holdings, they pursued a measured approach—subdividing former nursery lands incrementally over several decades. Historic maps, such as Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps and Rochester Plat Maps, clearly illustrate this evolution: expansive nursery fields gradually giving way to streets, houses, and supporting infrastructure by the early twentieth century. Throughout this period of change, the park remained the organizing feature, anchoring development and shaping neighborhood identity.

This development period ultimately extended into the mid-twentieth century, with the creation of many of the residential areas surrounding Highland Park, as well as other smaller developments throughout the city, including Birch Crescent and portions of the Maplewood neighborhood. The resulting neighborhoods reflected this long evolution. Streets were laid out gradually, lot sizes varied, and architectural styles shifted over time, creating cohesive but diverse residential areas. Former nursery grounds became home to what are today known as the Highland Park, Azalea, and Mt. Hope–Highland neighborhoods—each shaped by its proximity to green space and by Ellwanger & Barry’s careful stewardship of the land. The Ellwanger & Barry Realty Company’s active role in development concluded in 1963 with its final liquidation.

Unlike speculative subdivisions elsewhere, these neighborhoods retained a strong connection to their landscape origins. Streets followed natural contours, mature trees were incorporated into development, and homes reflected changing architectural trends from the mid-nineteenth through the mid-twentieth centuries. The proximity to Highland Park—and to its carefully integrated natural and engineered features—became a defining asset, reinforcing a sense of place that remains evident today.

Ellwanger & Barry residential development on Rockingham Street ca. 1920. Image courtesy of Ellwanger and Barry Papers collection at the University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, box 4.

A Living Landscape and Lasting Legacy

Today, Highland Park encompasses approximately 150 acres and remains one of Rochester’s most beloved public spaces—home to year-round recreation, significant horticultural collections, a municipal reservoir that also serves as a scenic landscape feature, and the annual Lilac Festival. Equally important are the surrounding neighborhoods of Highland Park, Azalea, and Mt. Hope–Highland, where historic homes and tree-lined streets continue to reflect Ellwanger and Barry’s long-term vision.

This interconnected landscape of park and neighborhood is formally recognized through its listing in the National Register of Historic Places, acknowledging its significance for landscape architecture, community planning, and its association with Ellwanger & Barry’s nursery and real estate enterprises. More than a park, and more than a neighborhood, Highland Park represents a rare example of how horticulture, infrastructure, philanthropy, and planning came together to cultivate community—leaving a legacy that continues to shape Rochester’s landscape today.

January sunrise at Highland Park Reservoir. Photo courtesy of Megan Hillyard.